LENGUAJE

Inhibitory Mechanisms in Negation

The primary communicative role of negation is to reject or otherwise correct specific information. But which brain mechanisms and cognitive processes allow words like “no” or prefixes such as “in-” to serve this purpose? Recent accounts suggest that linguistic negation relies on the reuse of domain-general mechanisms involved in conflict monitoring and inhibitory control. In our research group, we use electroencephalography and transcranial magnetic stimulation to test two central predictions of this hypothesis: 1) does negation involve the inhibition of the brain representations of the negated information?, 2) does this physiological effect depend on general-purpose brain mechanisms shared with other cognitive processes, such as action inhibition?

Recent publications:

Beltrán, D., Morera, Y., García-Marco, E., & Vega, M. D. (2019). Brain inhibitory mechanisms are involved in the processing of sentential negation, regardless of its content. Evidence from EEG theta and beta rhythms. Frontiers in psychology, 10, 1782.

Beltrán, D., Liu, B., & de Vega, M. (2021). Inhibitory mechanisms in the processing of negations: A neural reuse hypothesis. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research, 50(6), 1243-1260.

Liu, B., Gu, B., de Vega, M., Wang, H., & Beltrán, D. (2024). Existential negation modulates inhibitory control processes and impacts recognition memory. Evidence from ERP and source localisation data. Language, Cognition and Neuroscience, 39(2), 265-277.

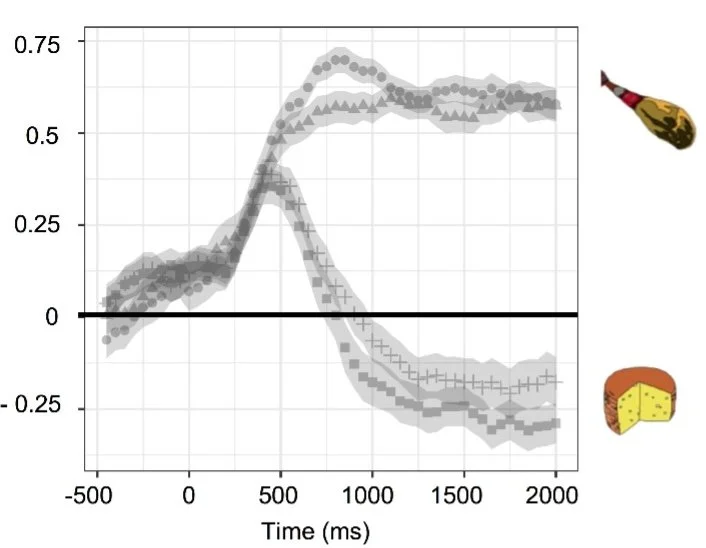

Negation-Induced Forgetting

If understanding negated information, for example, “The robber’s hair was not curly,” involves suppressing or inhibiting that information to some extent, it is worth asking whether, once processed, that information becomes less accessible over time than if it had been stated affirmatively, for example, “The robber’s hair was curly.” Recent studies suggest that this is indeed the case, showing that negated information is more easily forgotten than affirmed information. Much of our current research therefore focuses on two goals: (1) examining the scope and long-term implications of this negation effect, and (2) determining whether it is driven by inhibitory mechanisms or by associative interference.

Recent publications:

Zang, A., Beltrán, D., Wang, H., Rolán, K., & de Vega, M. (2023). The negation-induced forgetting effect remains even after reducing associative interference. Cognition, 235, 105412.

Martín, S., Orenes, I., & Beltrán, D. (2024). Negation-induced forgetting: Assessing its extent and the involvement of inhibitory processes. XXIV Congreso Nacional de la Sociedad Española de Psicología Experimental, Almería.

Beltrán, D., Zunino, G., & Hinojosa, JA., D. (2024). Misconceptions and active denial might be critical for negation-induced forgetting. XXIV Congreso Nacional de la Sociedad Española de Psicología Experimental, Almería.

New Word Acquisition

Even in adulthood, learning new words remains an ongoing process, whether in our native language or in a second language. Identifying the factors that shape this growth of the lexicon is one of the core questions driving our research. To this end, we use electroencephalography to investigate how new word learning is influenced by: 1) the number of repetitions, 2) exposure within semantic and linguistic contexts, 3) proficiency in the language to which the words belong, and 4) their association with specific emotional stimuli, such as disgust and sadness.

Recent publications:

Bermúdez-Margaretto, B., Beltrán, D., de Vega, M., Fernandez, A., & Sánchez, M. J. (2024). Syntactic and emotional interplay in second language: emotional resonance but not proficiency modulates affective influences on L2 syntactic processing. Cognition and Emotion, 1-9.

Fu, Y., Bermúdez-Margaretto, B., Beltrán, D., Huili, W., & Dominguez, A. (2024). Language proficiency modulates L2 orthographic learning mechanism: Evidence from event-related brain potentials in overt naming. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 46(1), 119-140.

Gu, B., Liu, B., Wang, H., de Vega, M., & Beltrán, D. (2023). ERP signatures of pseudowords’ acquired emotional connotations of disgust and sadness. Language, Cognition and Neuroscience, 38(10), 1348-1364.

“Through reasoning, we explore how language can open up new perspectives on the world and on ourselves.”

REASONING

Mental Models of Deduction

Deduction involves drawing a conclusion from one or more premises. Formal logic specifies the procedures and rules that ensure a valid deduction, whereas psychology seeks to explain how and why people reason deductively. Three broad psychological theories of deduction can be distinguished. Two of them propose that deduction relies on the application of mental rules that partially resemble those of formal logic or probability theory. The third argues that, as with other forms of inference, deduction consists of constructing and combining mental representations of the premises’ content. From this latter standpoint, known as mental model theory, our research has examined, and continues to examine, how people reason from conditional and negated premises, with particular emphasis on the factors that give rise to well-known illusory inferences.

Recent publications:

Espino O., Orenes, I., & Moreno-Ríos, S. (2022). Inferences from the negation of counterfactual and semifactual conditionals. Memory & Cognition, 50(5), 1090-1102.

Orenes, I., Moreno-Ríos, S., & Espino, O. (2022). Representing negated statements: When false possibilities also play in the mind. Journal of Cognitive Psychology, 34(8), 1052-1062.

Espino, O., Orenes, I. & Moreno-Ríos, S. (2024). Illusory inferences in conditional expressions. Memory & Cognition, 52, 1687-1699.

Moreno-Ríos, S., Orenes, I. & Espino, O. (2025). The temporal negation suspension strategy in Negative Conditionals. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology

Counterfactual Thinking

People do not only think about what actually happened; we also imagine alternatives to reality. In fact, we may spend more time thinking about what might have been or what could be than about what truly was or is. Expressions such as “I wish I had taken a taxi” or “If I had studied computer science, I would have a job now” draw attention to situations that did not occur and help us learn from experience and adjust our decisions and behavior. In our research group, we use eye-tracking methods to study how these expressions are understood and to examine their impact on other types of inference. If you would like to learn more about this line of research, we encourage you to watch this talk.

Recent publications:

Orenes, I., García-Madruga, J.A., Gómez-Veiga I., Espino O., & Byrne, R.M.J. (2019). The Comprehension of Counterfactual Conditionals: Evidence From Eye-Tracking in the Visual World Paradigm. Front. Psychol. 10:1172. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01172

Orenes, I., Espino O., & Byrne, R.M.J. (2022). Similarities and differences in understanding negative and affirmative counterfactuals and causal assertions: evidence from eye-tracking. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 75(4), 633–651.

Critical Thinking

From a more applied standpoint, we are developing interventions aimed at fostering critical thinking in educational settings. Our goal is to encourage analysis and reflection among the general public across a range of contexts, including learning to recognize cognitive biases, identify fake news, distinguish facts from opinions, and evaluate the quality of arguments.

Recent publications:

Villanueva, I., & Orenes, I. (2024). Assessing the impact of short critical thinking training sessions: active vs. passive learning. XXIV Congreso Nacional de la Sociedad Española de Psicología Experimental, Almería.